By Alana Scott.

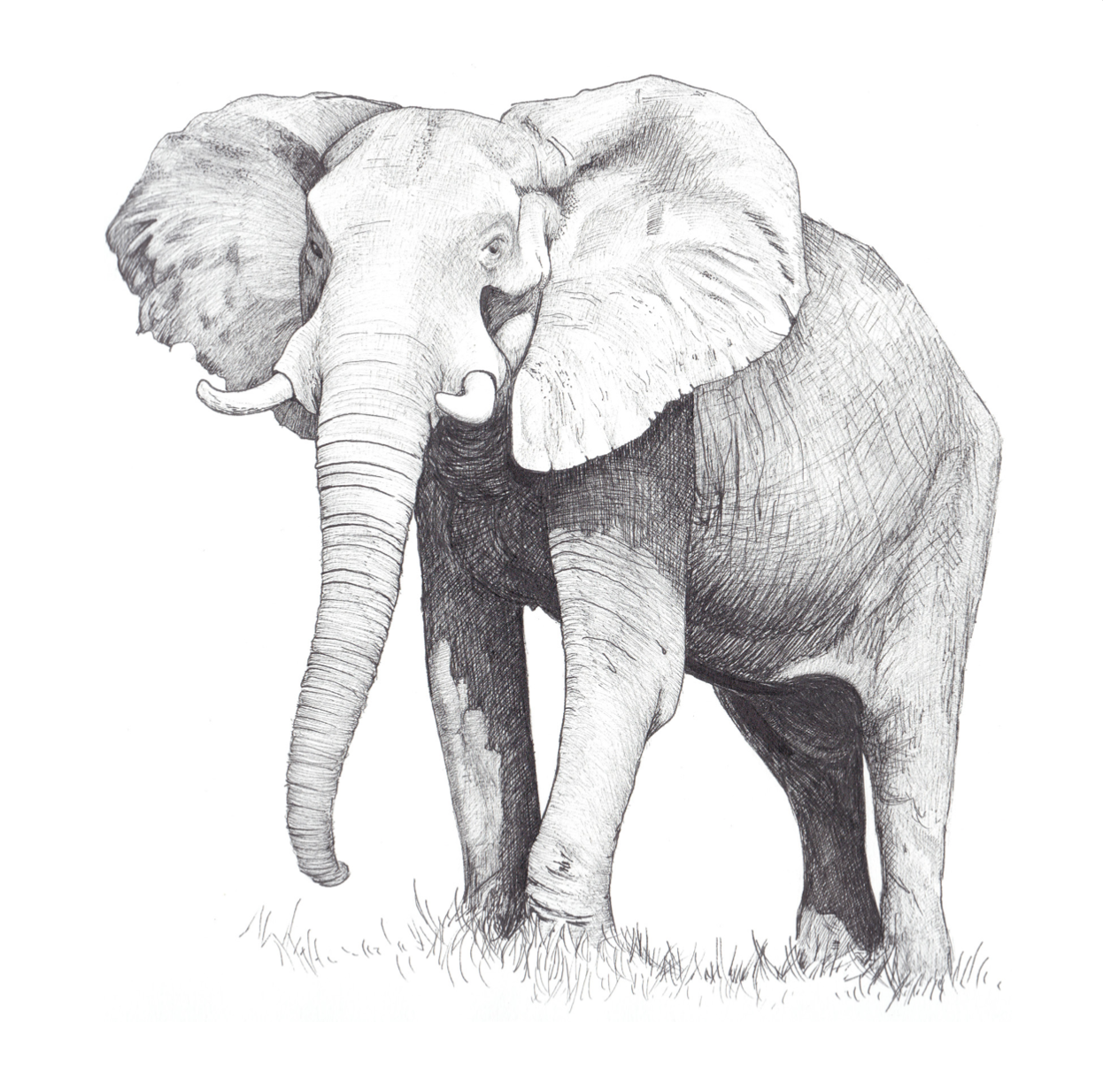

Wild beavers, like many other species, have been absent from England for centuries. Last sighted in the 16th century, beavers were hunted to extinction for their fur and castoreum — a secretion they use to mark their territories, which is also used by humans in food, perfumes, and medicine. Yet beavers are far from being just another forgettable species lost from our countryside. They are one of nature’s most ingenious engineers, and their architecture provides more than just new homes; it creates new life.

Beavers construct dams in order to plug fast flowing rivers, causing water to expand into the nearby area and creating a species-rich wetland. For the beavers, this generates a pond within which they can build a dry lodge, providing themselves with underwater getaway opportunities in the case that a predator is on the prowl. For the majority of other life forms, the new wetland is a source of food, water, and habitat — a major boon for biodiversity. Frogs and toads lay their spawn in the shallows, whilst water beetles skim across the surface. Crane flies, dragonflies, and other insects hover over the water, attracting breeding fish and insectivorous birds such as warblers. Rare mammals, such as water voles and otters, also benefit greatly from the new habitat. Yet it’s not only water-dwelling wildlife that benefits from the busy building of beavers. As beavers fell trees to construct their dams, they create clearings in closed-canopy woodland, which are soon colonised by less dominant plant species. Glades of wildflowers bloom, attracting bees, butterflies, and other important pollinators, which in turn supports a vast network of both common and endangered species.

Large European beaver dam. Photo: Lars Falkdalen Lindahl.

It’s not surprising that a government hesitant to make radical environmental changes is also reluctant to release these resourceful rodents. In addition, their release is strongly opposed by farmers and fishermen, who believe that beavers will either flood their fields or eat their fish. Though the latter is a completely unfounded misconception (beavers are herbivores, whose diets mostly consist of leaves, tree bark and aquatic plants), the former holds some truth; beavers often build their dams up-river, creating flooded wetlands in areas which could coincide with agricultural fields. However, these wetlands act as a buffer to the flooding of towns and agricultural land further down-stream, significantly slowing the rate of flooding in higher-risk areas. Overall, flooding is reduced in a much more cost-effective and environmentally friendly manner than the government could do with hard engineering solutions.

Despite these oppositions, slow progress in the realm of reintroductions is still being made. In 2009, the first trial reintroduction of beavers occurred in Scotland. Simultaneously to the trial period, beavers were released illegally to another part of Scotland and started to rapidly expand and colonise the area; by 2016, the Scottish government announced that beavers could remain in the country as a wild, protected species, though no more could be reintroduced. However, the story of beavers in England is not quite as successful. The only free-living beavers are on the ironically-named River Otter, and these are closely monitored. From Cornwall to Cheshire, aspirational beaver projects are being set up to demonstrate the potential beavers have for creating vibrant wetlands and reducing flooding, yet still, the government refuses to release them. With everything to gain and nothing to lose, what are they waiting for?

After all, even a politician could enjoy the sight of a beaver swimming freely through our rivers, its silhouette slipping silently into the water while around it, barren landscapes are transformed into biodiverse symphonies.

Find more from Alana on Instagram - @ecologistalana

the range…

Click here to view our Beaver range. 10% of the sale price of products in this range will go to support the Beaver Trust.

Take a look at our current designs:

Humboldt penguins are classed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN list but are listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ in Peru. There has been a huge overall drop in numbers of the past 100 years, where Humboldts originally were estimated to be in numbers of almost one million and have since dropped to only 30,000 individuals.

One of our new designs is the lesser spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos minor. I'm sure some of you are not very familiar with this bird and that is one the main reasons we have chosen it for our new designs. To raise awareness and funds for it's much needed conservation.