A century ago, the number of wild tigers roaming the earth was thought to be around 100,000 individuals. Fast forward to 2010, numbers plummeted to hit an all-time low of around 3,200. That same year International Tiger Day was created, and is now celebrated each year on 29th July. It was founded by the 13 tiger range countries that came together to create the TX2 goal; a global commitment to double the number of wild tigers by 2022, the next Chinese Year of the Tiger. After a 100 years of decline, tiger populations are now increasing in some of these countries, including India, Nepal, Bhutan and Russia. There’s an estimated 3,900 tigers in the wild, but a lot more work is needed to be done in order to secure their future.

Across their now reduced range, tigers face numerous pressures. Currently it’s believed tigers occupy a mere 4% of their former range. Their habitats have been destroyed, degraded and fragmented by human activities. Forests have been cleared for agriculture and timber production, as well as road networks and other building developments that further fragment the already decimated landscapes. Tigers are very territorial creatures with large home ranges, so wider habitats are needed for survival. Small, scattered islands of suitable habitats means there is a higher risk of inbreeding, and its more likely tigers with cross paths with poachers as they wander out of their protected areas to establish larger territories.

Tigers are now competing with humans for space. By shrinking the size of forests, there’s no longer enough prey available in the area to support the tigers. They consequently have to venture into human-dominated areas that lie between habitat fragments and hunt the domestic livestock that local communities depend on. In retaliation for this, tigers are either killed or captured to be sold in black markets.

Poaching is a huge threat to their numbers, with every part of a tiger being sold in illegal wildlife markets. These body parts and bones are often used in medicines and their skins are seen as status symbols in Asian cultures. The battle against poaching is made increasingly difficult in countries with limited resources for guarding protected areas where tigers live. Enormous profits can be gained from wildlife crimes, making it an extremely desirable risk for criminals around the world.

To save tigers, forest and grassland habitats need to be secured across Asia. By protecting large, biologically diverse landscapes, tigers are able to roam and many other threatened species can be preserved. In order to protect one tiger, 10,000 hectares of forest need to be conserved.

Supporting Tiger Conservation Efforts

The Wildheart Trust is a registered charity which is dedicated to realising its global ambitions to make a meaningful impact on the health of the natural world while actively improving the well-being of animals in human care. The Trust runs the Wildheart Animal Sanctuary and provides governance for its conservation aims.

For a number of years they have chosen to specialise in tigers and have three individuals at their sanctuary. They are not involved in any breeding programmes at present, as their tigers come from problem backgrounds with impure or unknown bloodlines. Instead, they offer their individuals a happy and safe forever home after being rescued from abuse. They hope to educate and inspire their visitors into caring about efforts to protect them.

Conservation is one of the main aims of The Wildheart Trust’s mission, and they want to do everything they can to protect the animals we all love in their natural environment, safeguarding their futures. They provide funding to support an in-situ tiger conservation project called ‘Supporting Local Advocacy for Tiger Conservation in the Bhadra-Kudremukh Landscape’, which is managed in India by the Wildlife Conservation Society.

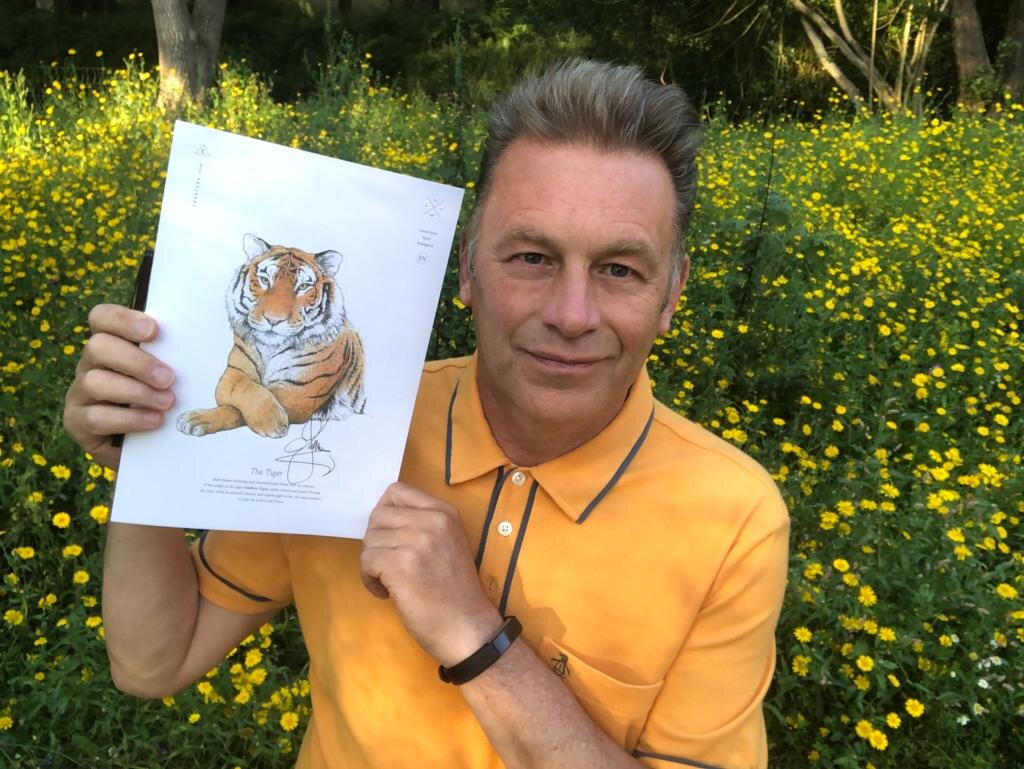

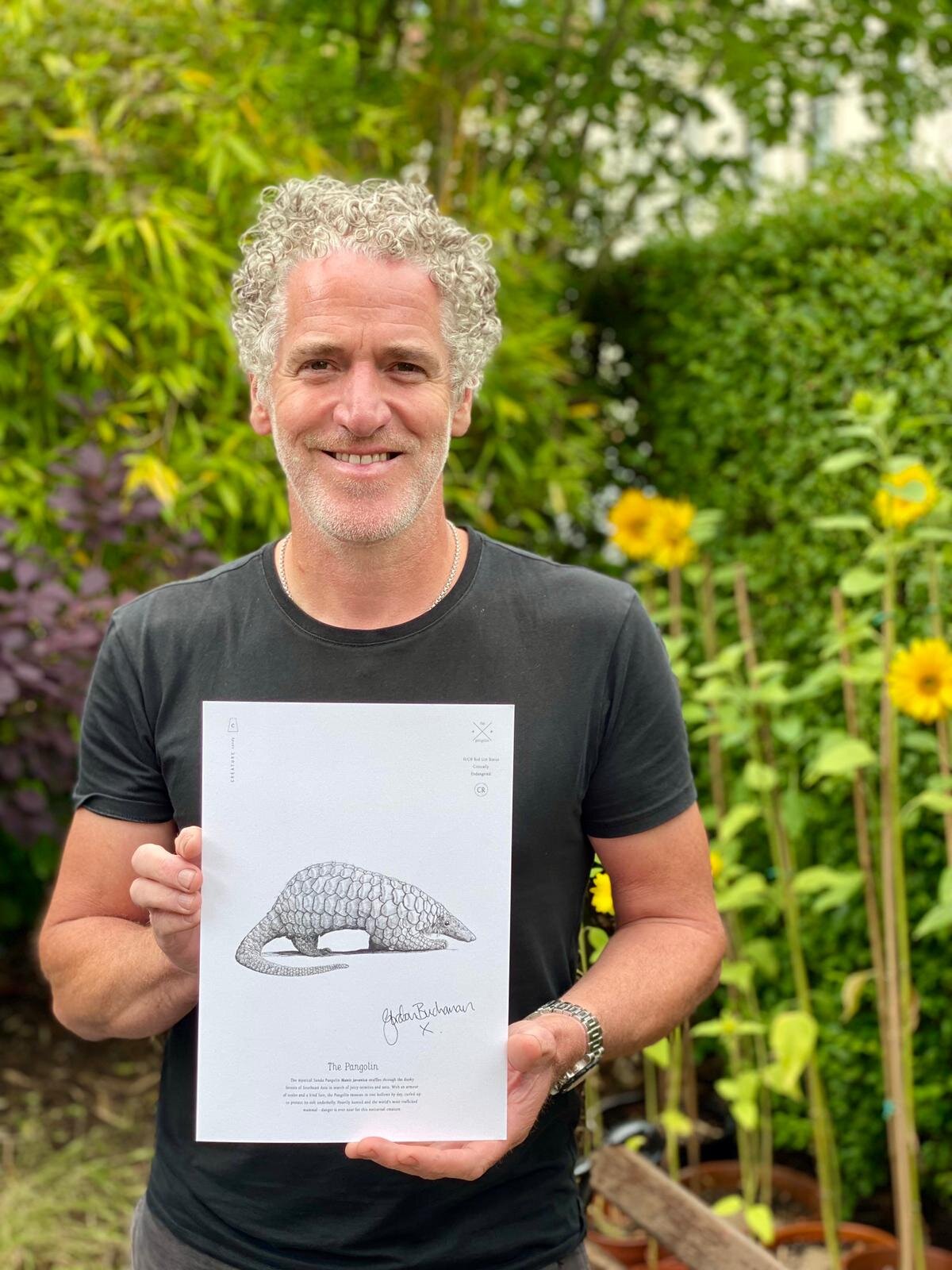

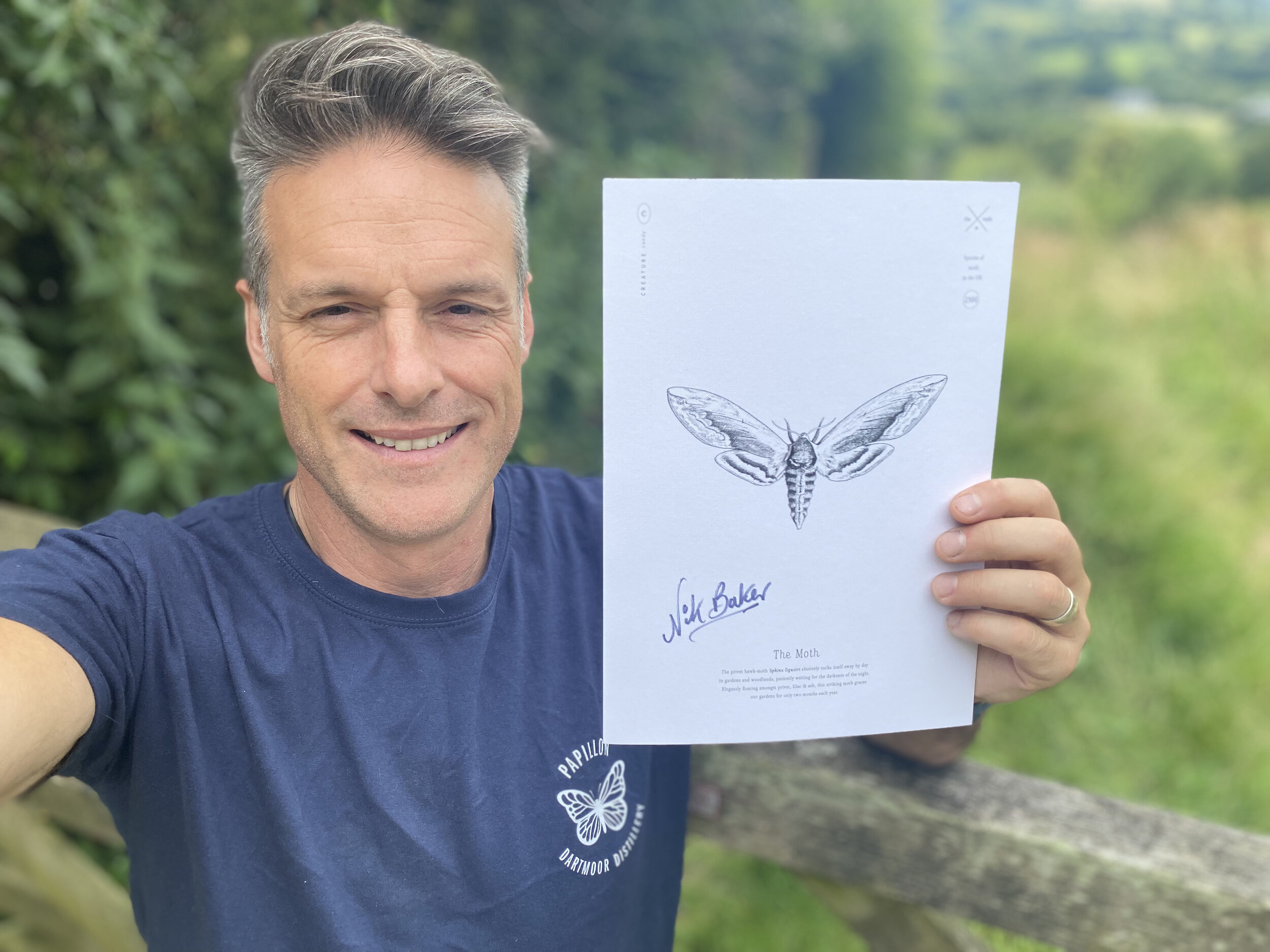

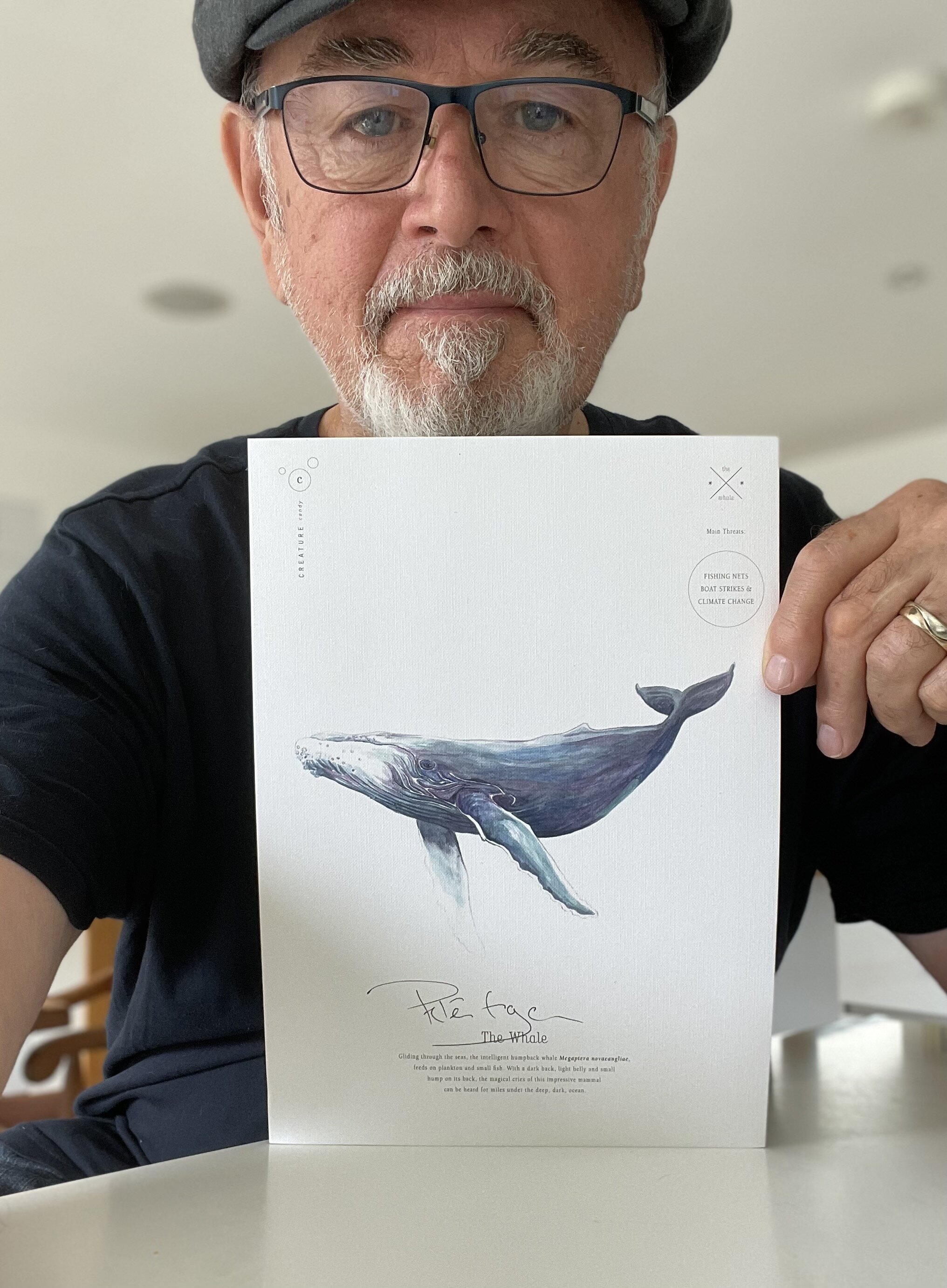

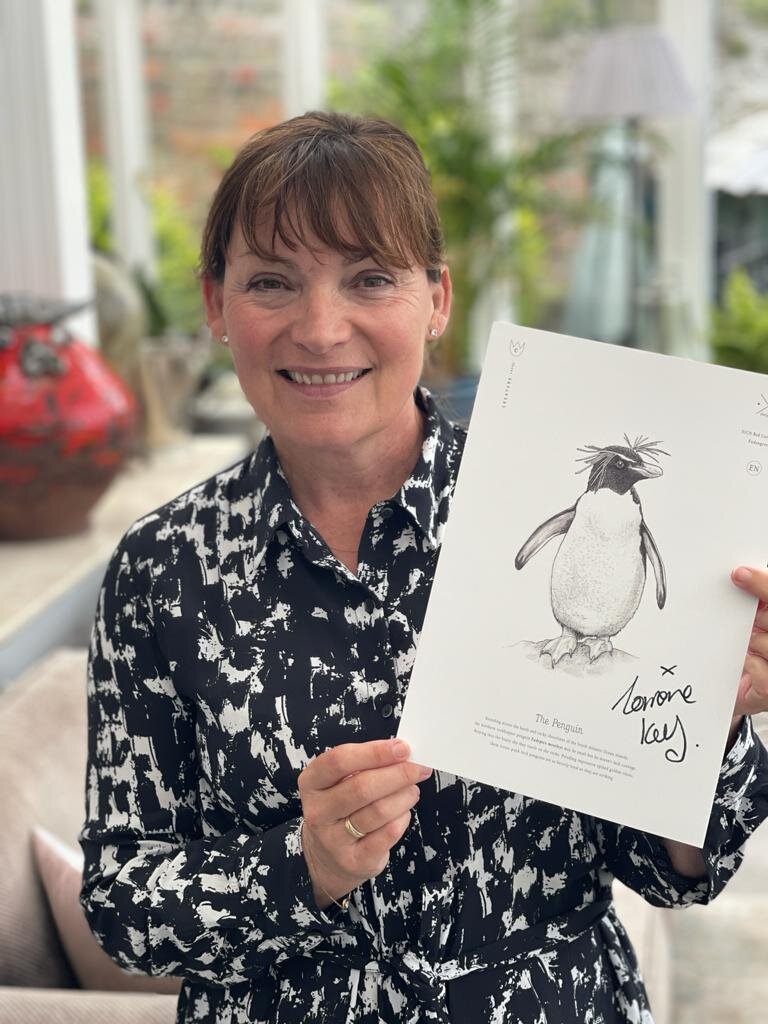

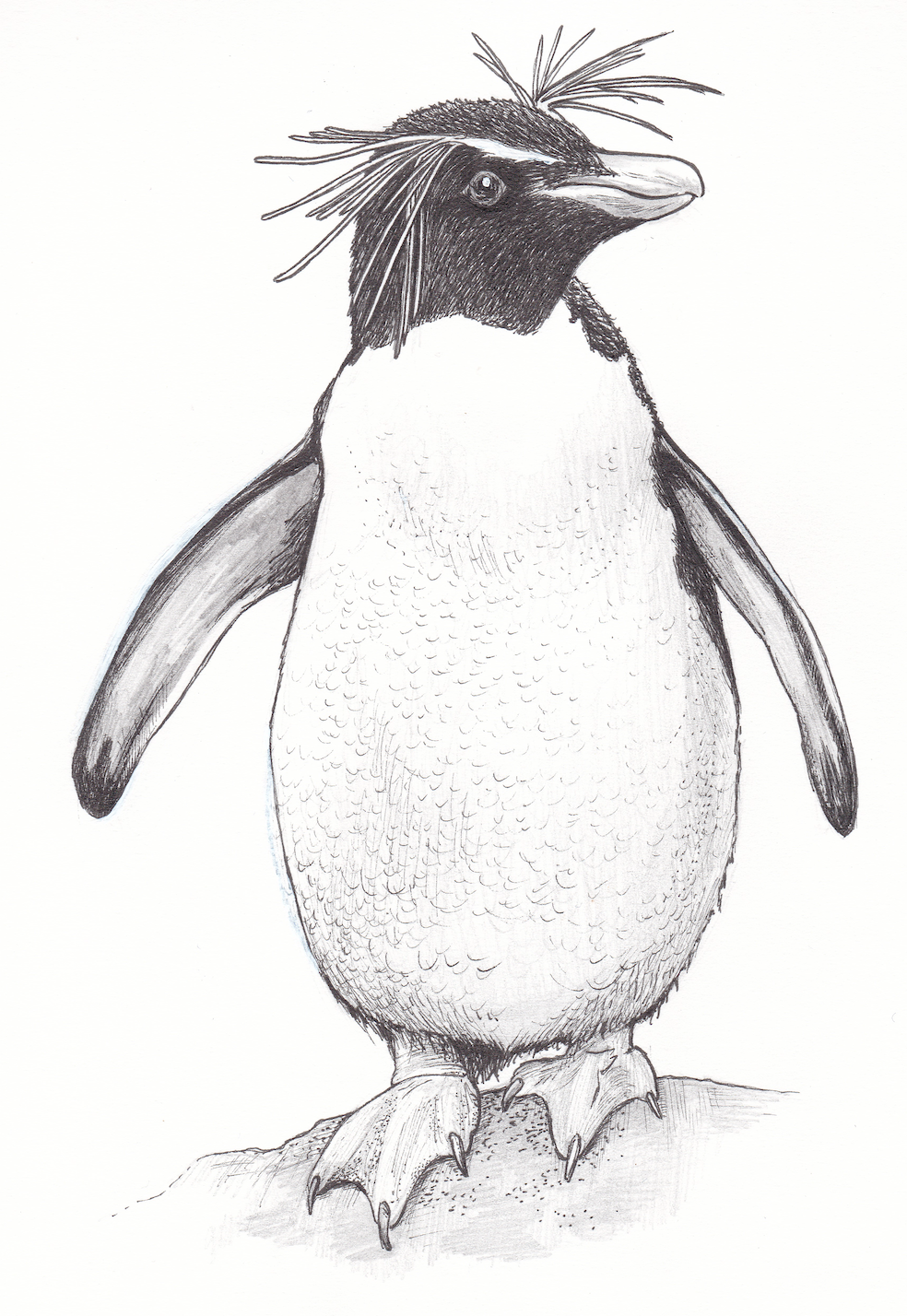

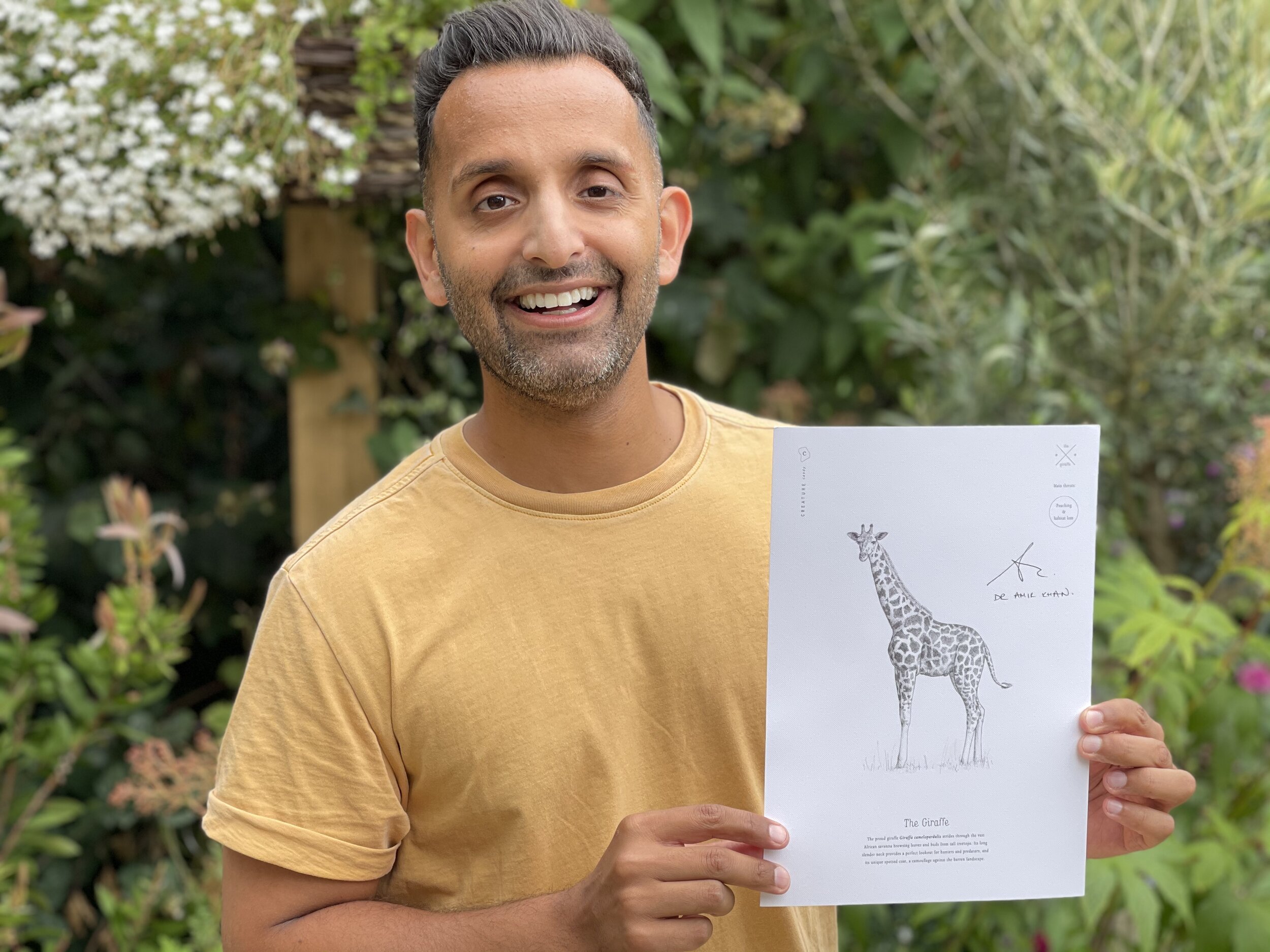

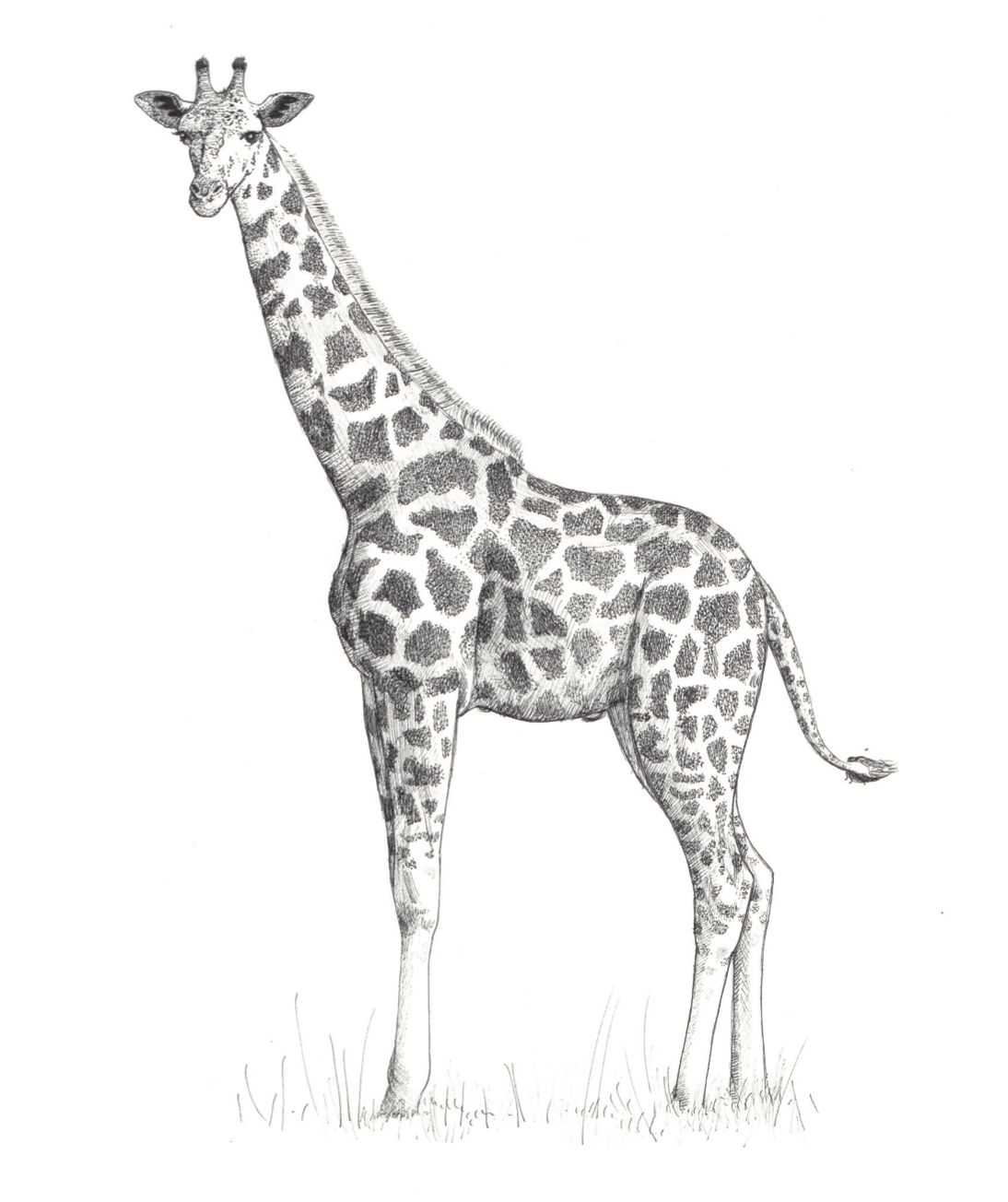

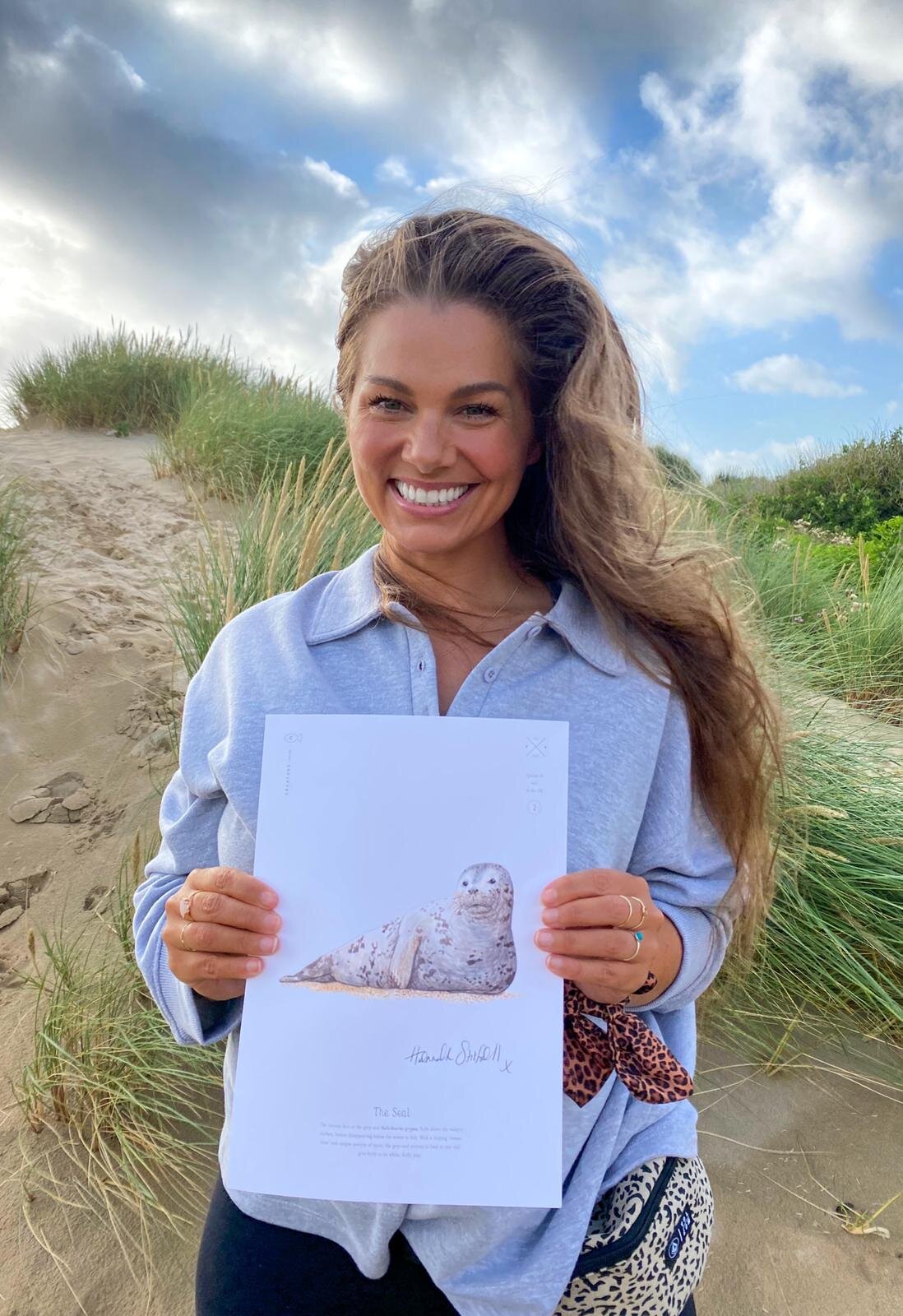

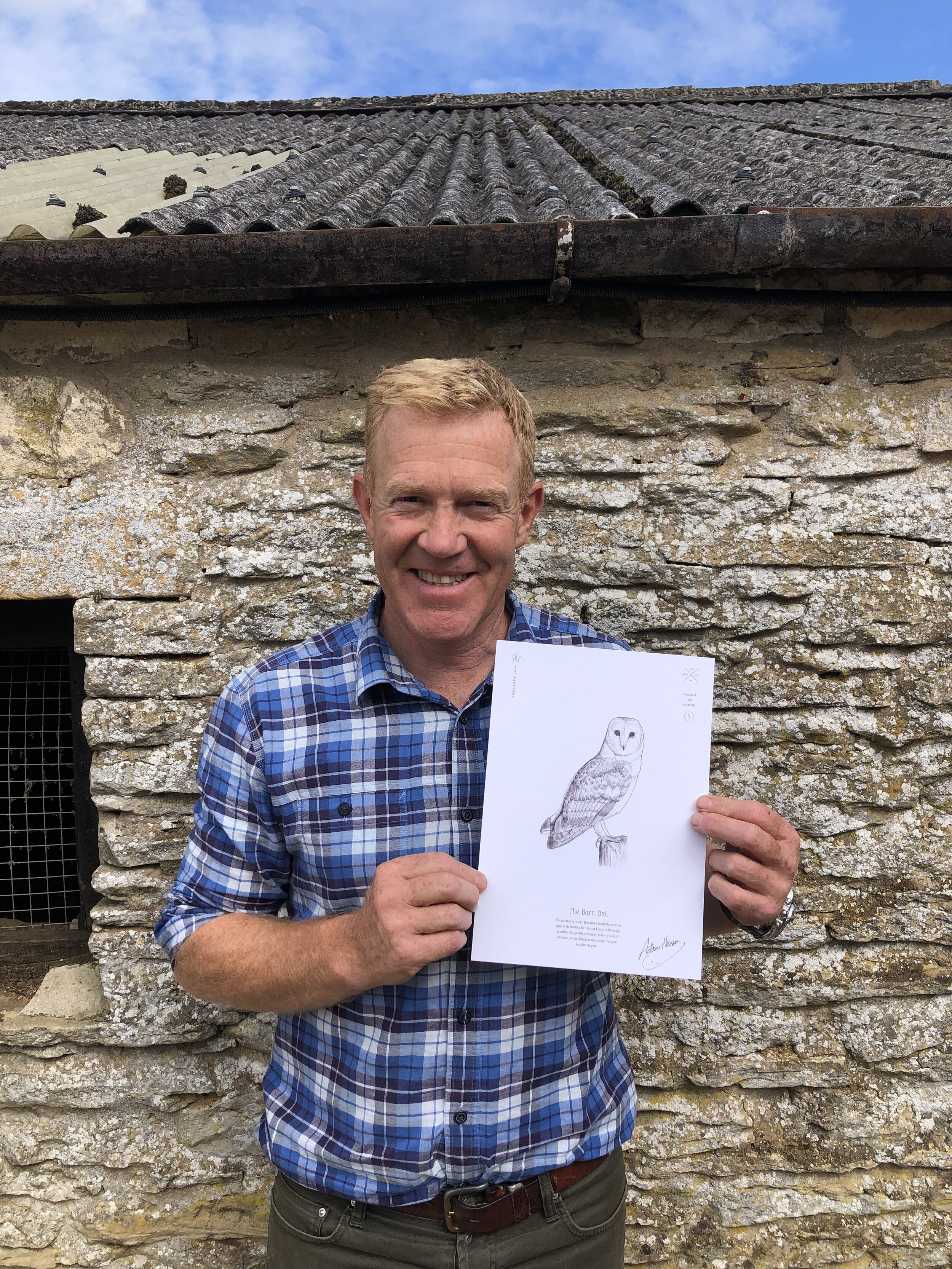

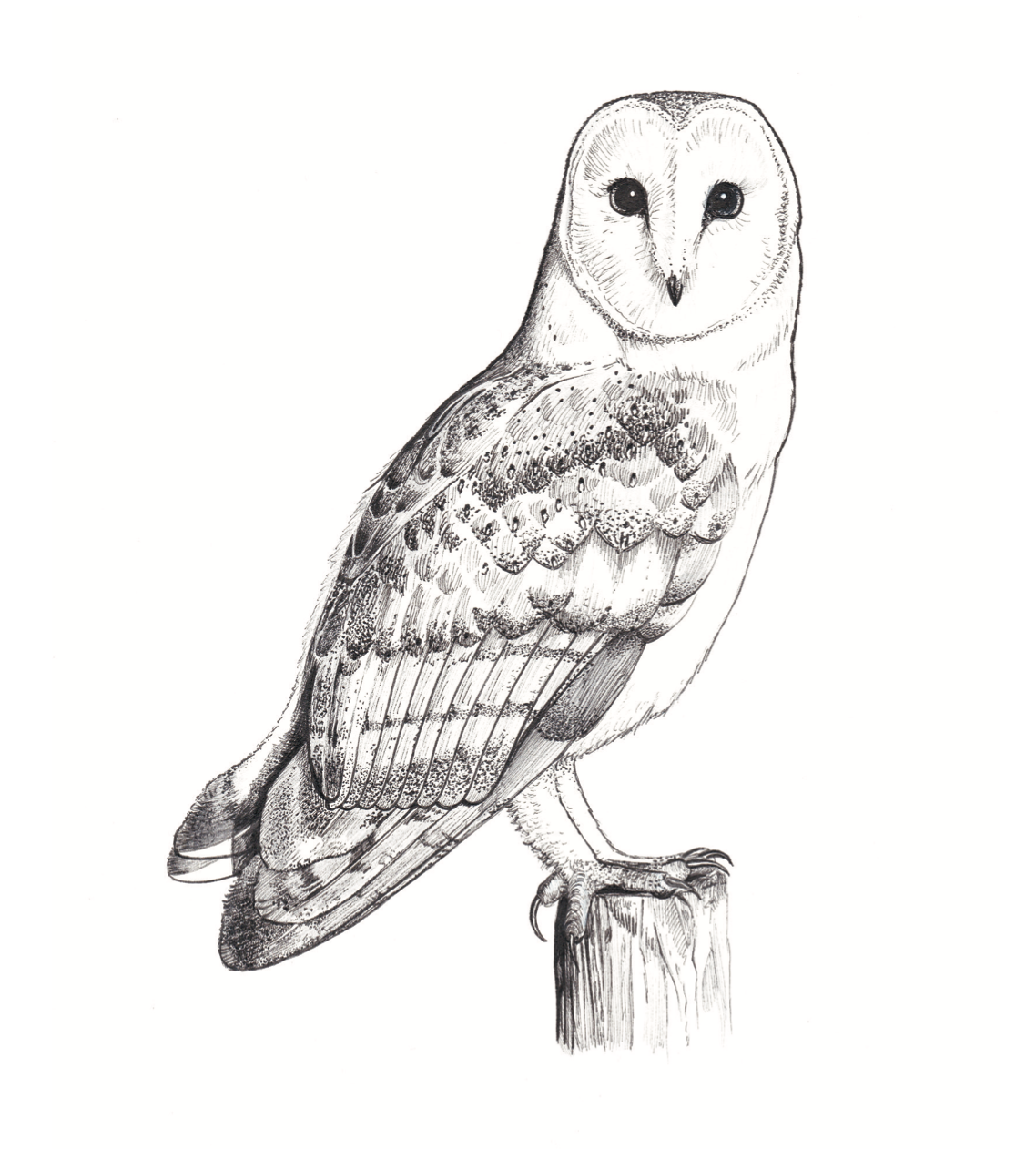

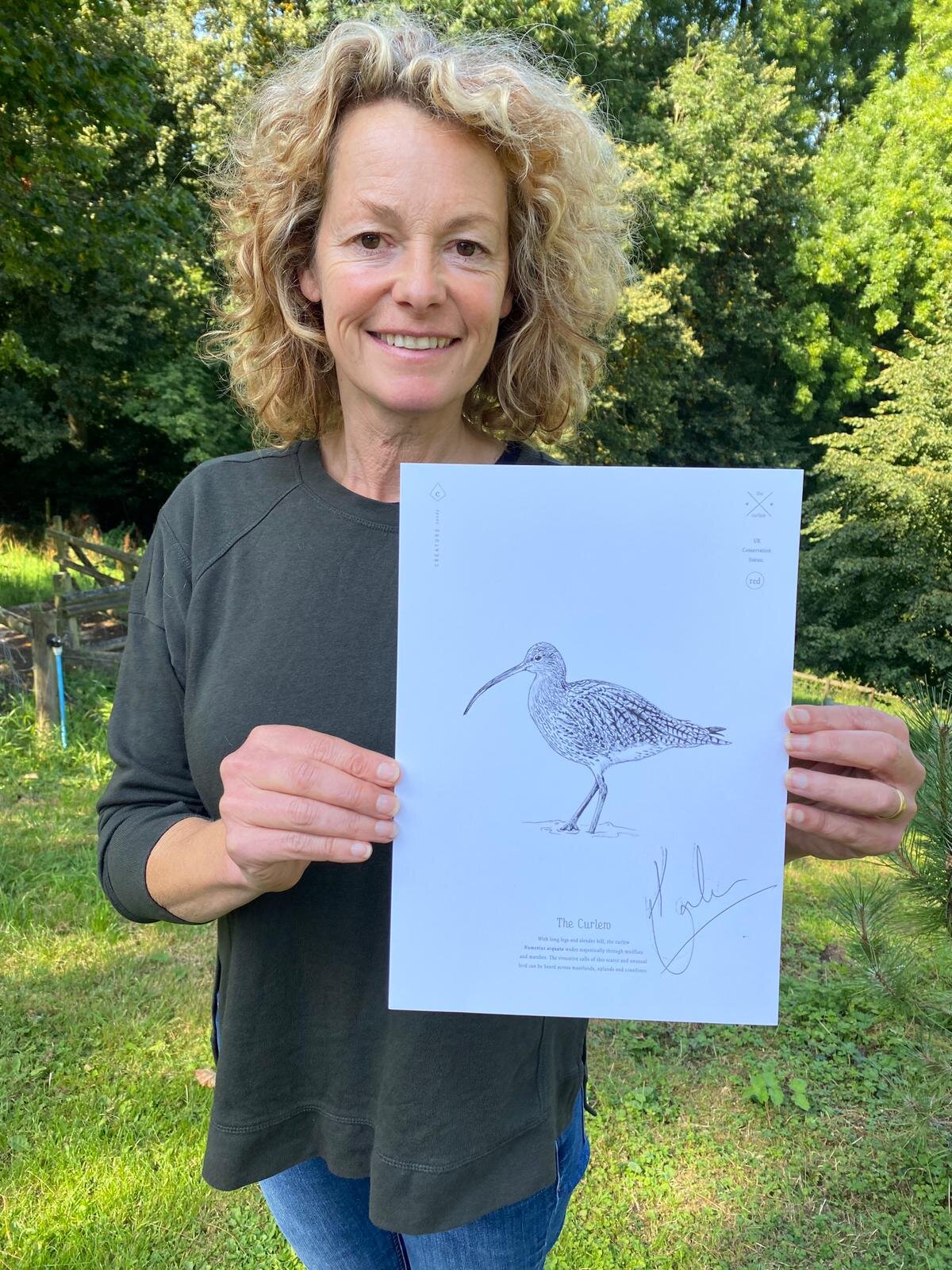

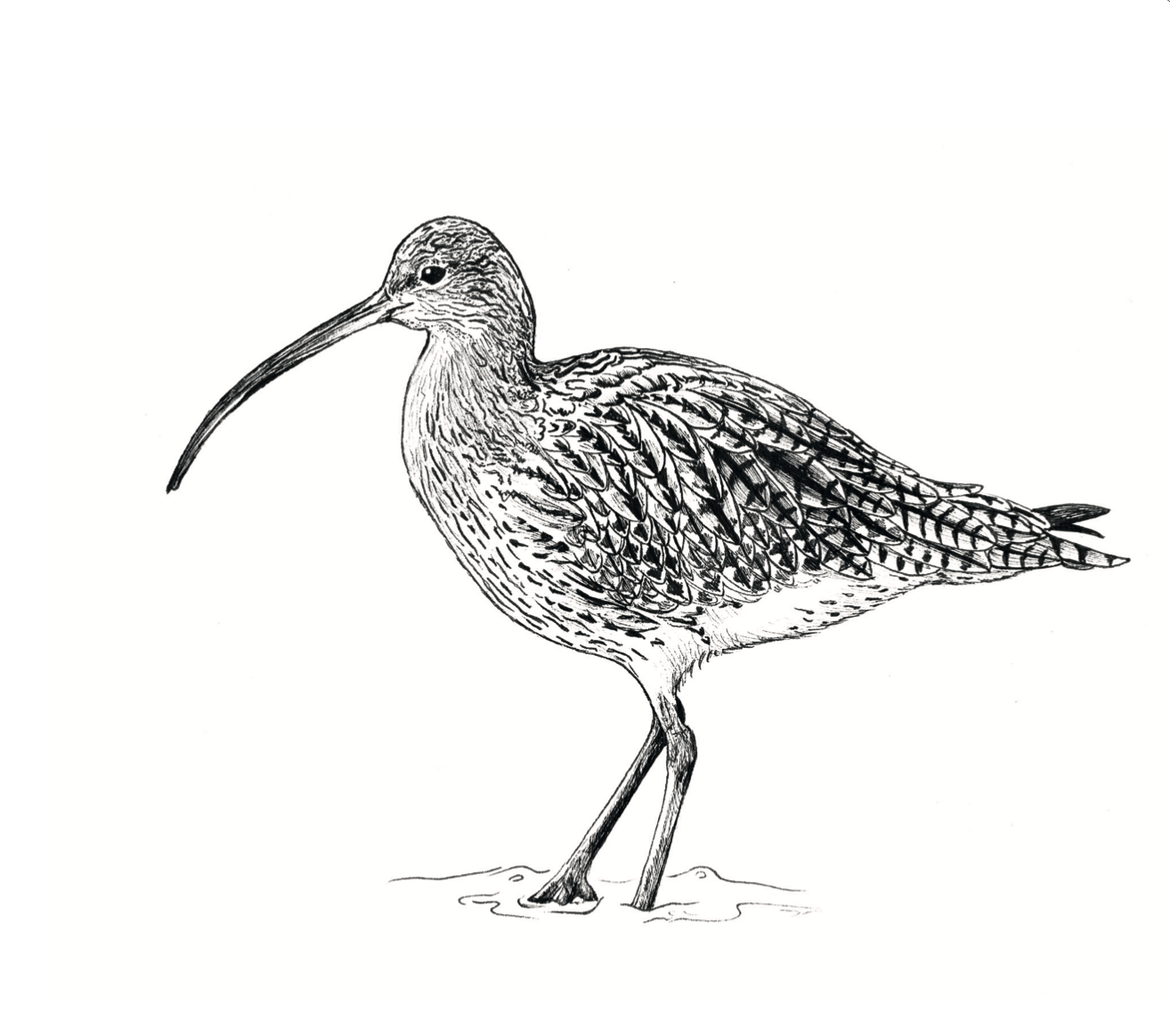

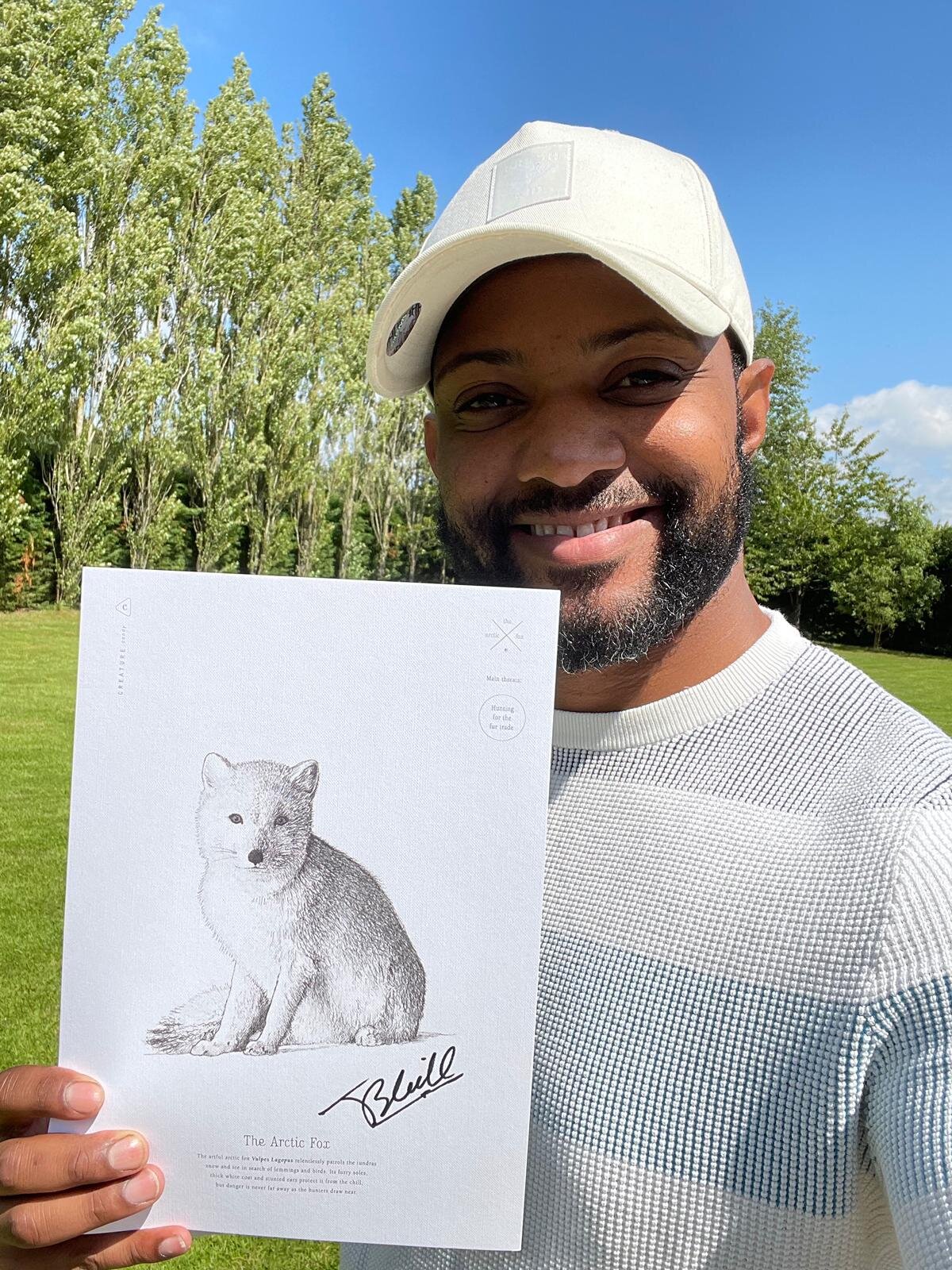

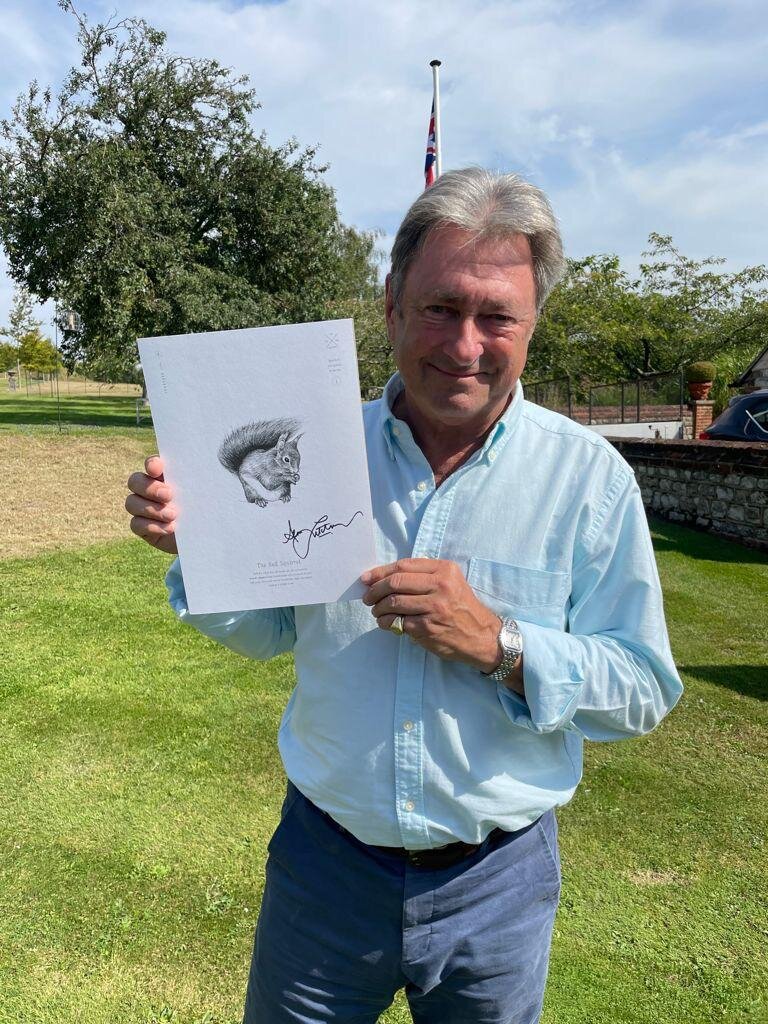

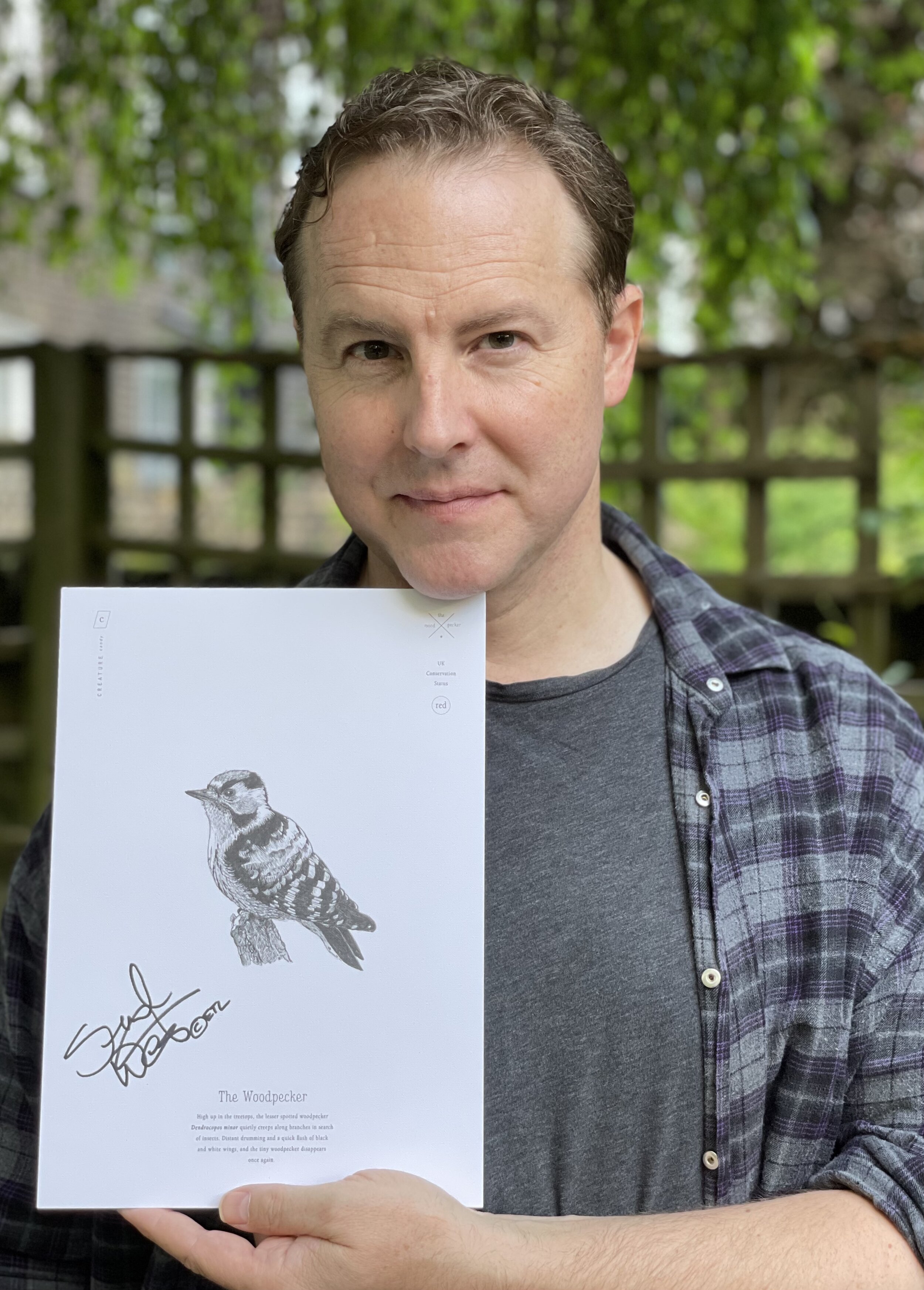

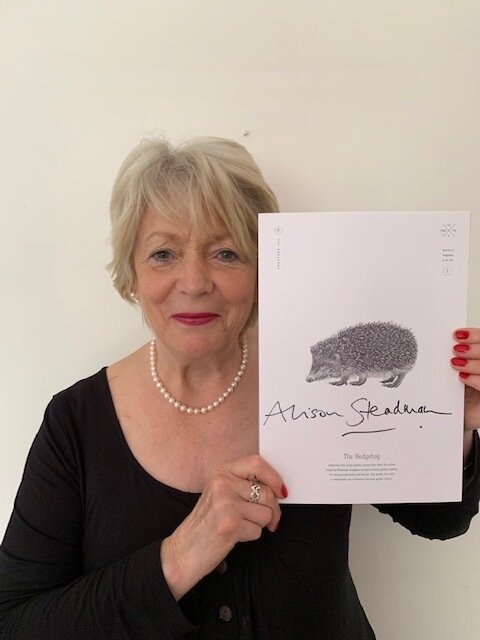

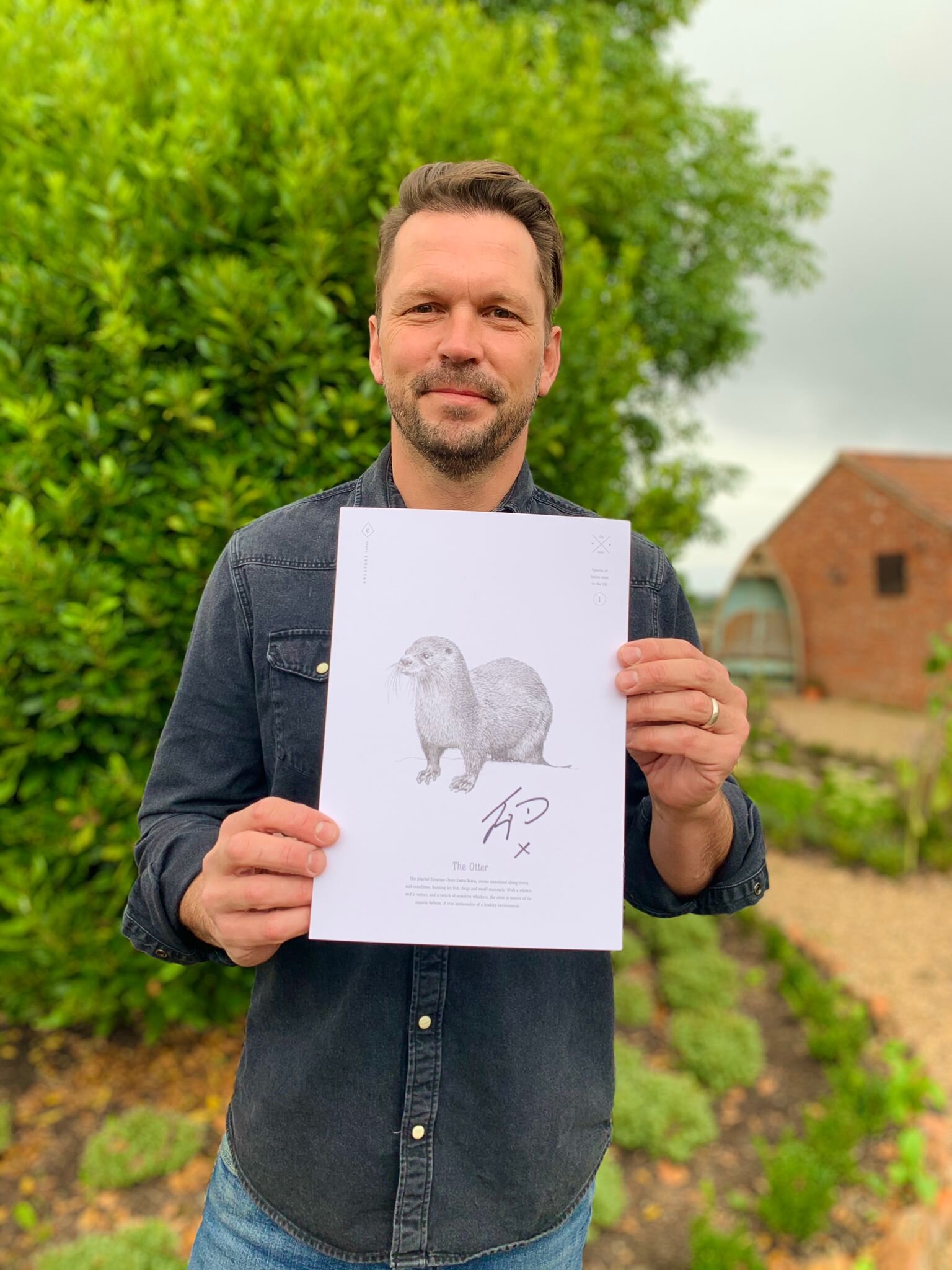

Here at Creature Candy, we have been inspired their dedication for tiger conservation and have created a tiger range for The Wildheart Trust, with 10% of the sale of all products in this range donated to them to help fund the incredible work they do. We also have an upcoming campaign, the ‘Big Fundraiser for Wildlife 2021’, where 100 of our tiger prints will be signed by Chris Packham (a trustee of The Wildheart Trust) and will be up for grabs for £25 each, with 50% of the sale price being donated to The Wildheart Trust. The campaign will launching on Monday 9th August 2021, find out more information about all the supporters and designs involved here, and sign up to our mailing list to be the first to find out when the prints go on sale!